The best literature on innovation all points to the same thing: innovation is highly uncertain, and therefore the best approach is to experiment and prototype, iterating until you find the right product/market fit, and conduct this iteration with the diligence of the scientific method. The advice is so consistent, yet when we look at innovation metrics, there is rarely any kind of KPI measurements around the details of experimenting and prototyping. Let’s look at why it’s so important, and what a KPI might look like.

Fire bullets, then cannonballs (Jim Collins)

In Great by Choice, Jim Collins describes the idea of firing bullets, then cannonballs. Very rarely is an innovation a big single shot, but rather it’s the outcome of many smaller steps that helped to calibrate towards that right outcome. When Apple moved into retail stores, they started with one shop, prototyping, firing bullets to see what hits; when they got it right they expanded, and became the most profitable per square feet retailer in the world.

What makes a bullet?

- A bullet is low cost. The size of the enterprise determines what low cost means, a cannonball for a $1 million enterprise might be a bullet for a $1 billion enterprise.

- A bullet is low risk. That doesn’t mean low probability of success, but it means minimal consequences if the bullet hits nothing.

- A bullet is low distraction. It might be high distraction for a few individuals working with it, but for the enterprise as a whole, it’s very low distraction.

The behaviors you need to develop to be successful:

- Ensure you are firing enough bullets. They should be low enough cost and risk to allow for many.

- Resisting the temptation to fire uncalibrated cannonballs. Innovation is not about plowing money into big bets without the data to prove the investment.

- Committing fully when ready: by converting bullets into cannonballs once you have the empirical validation.

Disciplined Experimentation (Govindarajan and Trimble)

In The Other Side of Innovation, authors Govindarajan and Trimble go to great lengths to describe how to organize yourself for innovation, and how generating ideas is the least difficult part. Execution on ideas is where you need to focus, and the fundamental ingredient is the ability to experiment in a disciplined way.

In managing their ongoing operations, companies strive for performance discipline. For the innovation initiatives, however, they ought to strive for discipline of a different form: disciplined experimentation. Indeed, all innovation initiatives, regardless of size, duration, or purpose, are projects with uncertain outcomes. They are experiments.

For an idea to mature, it must start with an experiment. Create a plan, with a scorecard, which explains the assumptions, and the data points you will measure. Formalize a clear hypothesis, in very simple terms, which states what you think will happen. Then find ways to spend a little, but learn a lot. Keep assessing the plan as you go, and allow formal revisions to the predictions you made.

…the scientific method is the innovator’s indispensable friend … when running innovation initiatives, businesspeople need to behave more like scientists.

Source: The Other Side of Innovation

The 5×5 Methodology (Michael Schrage)

In Michael Schrage’s excellent book, The Innovator’s Hypothesis, he believes experimentation is the difference between those that innovate, and those that don’t.

Look carefully at the history of technology, entrepreneurship, or business innovation. A persistent pattern emerges. Successful innovators talk about ideas, but they invest their time, money, and ingenuity in expressive experimentation. Their competitive success comes from getting more value faster from expressive experimentation.

Ultimately, what you’re seeking is insight, so that you can get closer and closer to an innovation; you want to buy a dollar’s worth of innovation insight for 50 cents, or 20 cents, or less. Fast and cheap, but an extremely high return on validated learning. His 5×5 methodology is designed to achieve this:

Give a diverse team of 5 people no more than 5 days to come up with a portfolio of 5 business experiments that cost no more than $5,000 (each) and take no longer than 5 weeks to run.

The results are then presented to a senior management board, and the best ideas get more funding to continue. The goal is to build a portfolio of experiments, but the problem is that most organizations just don’t know how to design or manage a portfolio of business experiments. The 5×5 methodology quickly gets you up and running.

Schrage provides extensive detail on how to run and measure the 5×5 method, along with compelling examples – it makes for tantalizing reading. It’s very easily attainable, and has enormous potential to build innovation muscle. But as he notes, big organizations find it incredibly hard to instill as a discipline:

Creating simple, compelling, and readily testable business hypotheses is managerially unfamiliar, uncomfortable, and unrewarding. So managers avoid them.

The DNA of an Innovator (Dyer, Gregersen, Christensen)

In The Innovator’s DNA, business gurus Jeff Dyer, Hal Gregersen and Clayton Christensen, analyze what makes an innovator. They define 5 skills that you need to master to become a disruptive innovator: Associating, Questioning, Observing, Networking, and …. Experimenting.

In their analysis they found that experimenting skills were significantly higher in innovators of all types, not just the start-up entrepreneurs, but also process innovators at large organizations.

Source: The Innovator’s DNA

One of the many example innovators in the study is Jeff Bezos, who puts the ability to experiment at scale at the heart of Amazon’s innovation strategy:

Bezos’s experience has taught him that experimenting is so critical to innovation that he has tried to institutionalize it at Amazon. “Experiments are key to innovation because they rarely turn out as you expect, and you learn so much … I encourage our employees to go down blind alleys and experiment. We’ve tried to reduce the cost of doing experiments so that we can do more of them. If you can increase the number of experiments you try from a hundred to a thousand, you dramatically increase the number of innovations you produce.”

To learn more about the five skills, and how to develop them, check this out.

Build, Measure, Learn (Eric Ries)

When The Lean Startup was published, it hit a home run. It nailed exactly the ethos and method for innovating in the 21st Century. Large corporates scrambled to figure out how to adapt it to their environment, and lean startup consultants appeared everywhere. The basic ideas are so simple and so effective though.

Generate a hypothesis, define a way to test it (build), define how you can strictly monitor it (measure), and define how to validate the results (learn). Then after each short cycle through that process, decide whether to persevere (do another loop with an adjusted hypothesis and new build), or pivot (move on to another hypothesis). It works for small incremental changes, and it works for whole product launches.

The essential lesson is not that everyone should be shipping fifty times per day but that by reducing batch size, we can get through the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop more quickly than our competitors can. The ability to learn faster from customers is the essential competitive advantage that startups must possess.

The Lean Startup works only if we are able to build an organization as adaptable and fast as the challenges it faces. This requires tackling the human challenges inherent in this new way of working.

To see the 10 methods of the Lean Startup, check this out.

Source: http://theleanstartup.com/principles

This is just a quick selection of some of the excellent literature out there, but many more exist which similarly stress the importance of experimentation, including The Innovator’s Method, Little Bets, and anything by Tom Peters (ready, fire, aim! And of course his ‘bias for action’ from In Search of Excellence).

Measuring Experimentation

So if experimentation is so widely regarded as the basis for innovation, why do we rarely see KPIs in place to track it? After all, what gets measured, gets done, right?

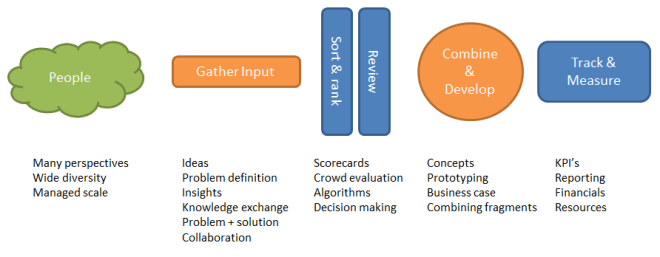

In the HYPE process, this is how it can be done. Let’s assume you’re using Idea Campaigns to generate high quality ideas, which target a known problem, with a sponsor who backs (and funds) selected ideas. Ideas are rarely ready for implementation right away, they need to be developed, or combined with other ideas, and then tested. This is where Concepts come in:

HYPE Enterprise process for full-lifecycle innovation management

With Concepts you can create customized processes and forms for managing the iteration and the evaluation steps. In the example below you can see a form included to track the iterations of a build, measure, learn cycle (Lean Startup). You capture the information for each iteration, then flag whether to pivot or persevere.

HYPE’s Concept feature allows for configurable process steps and data capture

The two critical KPIs are then:

- Number of experiments in my innovation portfolio (number of Concepts created)

- Number of iterations through those experiments (cycles through the build, measure, learn cycle)

Seeing these numbers go up over time, gives you a direct pulse on whether you are building innovation muscle. Providing you are following the scientific method, and seeking out validated learning, not just experimenting with no rigor.

Supporting these metrics, you’ll also want to know more granular details about the portfolio, such as:

- Number of experiments being run per “strategic innovation area,” to show you the health of each major area you’re targeting.

- Number of experiments by their status (pivot, persevere, or whatever other status you will determine for experiments).

- Number of experiments per organizational unit / business division / department, to help you understand what areas of the business are “getting it,” or struggling. Experimentation is not the exclusive domain of the innovation department, it should be part of the culture across the entire organization.

- You may also want to measure the time to cycle through an iteration. As Eric Ries notes, the question is how fast can you get through each loop, so that you’re learning faster and moving closer to the right outcomes?

We’re still spending a lot of time thinking about number of ideas, number of participants, and other rudimentary KPIs. These are nice to know, but they don’t tell you anything about your progress towards a more innovation-capable organization. The back-end is where the true health of your program is measured, and for that, we must measure and promote the experiments. As Michael Schrage nicely puts it in The Innovator’s Hypothesis:

Good ideas have nothing to do with good implementations … Implementation – not the idea – is the superior unit of analysis for assessing value creation. How organizations enact ideas – not the ideas themselves – is the soul and substance of innovation. More often than not, implementation ends up redefining both the boundaries and the essence of the original idea.

Are you tracking how you experiment? I’d love to know.

This article was originally published on the HYPE Innovation Blog.